At 60, Motown set to celebrate cultural legacy

In a year of expansion and commemoration for Motown, 60 years after its founding, there’s a renewed focus on the worldwide cultural impact that came out of the two-story house on Detroit’s near west side.

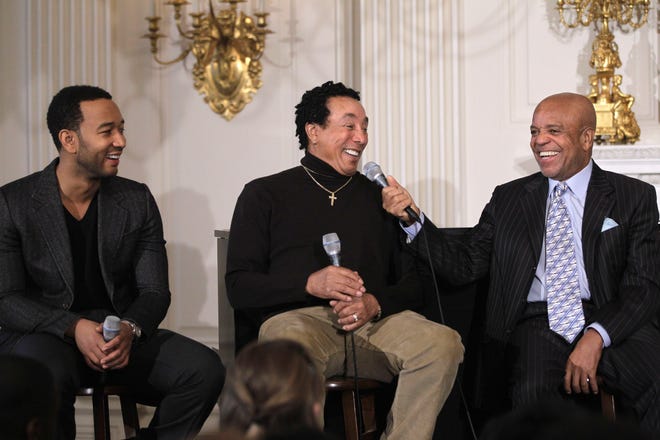

Earlier this year, an ambitious expansion of the Motown Museum was announced. On Sept. 4, it was revealed that Berry Gordy, the museum’s primary financial supporter, donated $4 million to the expansion fund, the single largest gift to the project. That adds to donations from Ford Motor Co. and UAW-Ford, AARP, DTE Energy, and nonprofits including the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and the Kresge Foundation. The project will build on the modest series of houses on West Grand Boulevard with a 50,000-square foot space that will include a theater and interactive exhibits.

But with expansion and corporate money, is there a danger that what made Motown special — its small size, gritty authenticity and do-it-yourself spirit — will be lost in such a big, glossy space?

“It can’t be. You know why?” said Robin Terry, Motown Museum's CEO and chairwoman. “That was the No. 1 thing people said to me — don’t change Hitsville (the original offices and recording studio). Our goal is, Hitsville is the diamond in the ring setting. Everything else just supports that crown jewel. It will always be that opportunity for our visitors around the world to step back in time. The other spaces allow you to explore music, be engaged in the story … but the crown jewel is sacred.”

The museum will present four days of activities Friday through Monday to honor the iconic Detroit label’s accomplishments, including a night of music and tributes, “Hitsville Honors,” Sunday at Orchestra Hall. Artists from the classic era, such as Mary Wilson of the Supremes, Martha Reeves, the Four Tops, and the Temptations, as well as contemporary Motowners KEM and Ne-Yo, and Detroit’s own Big Sean will perform and pay homage to Gordy and the worldwide phenomenon he started.

Why did Motown take root in Detroit, and not in Chicago or Cleveland?

Motown guitarist and Michigan native Dennis Coffey, who’s lived in Los Angeles and New York, believes it’s different here. Coffey provided the memorable wah-wah guitar line on the Temptations’ “Cloud Nine” during his years in Hitsville’s “Snakepit.”

“Music is in the DNA of Detroit," said Coffey. "Here, you have musicians who want to play it, people who want to go hear them, and club owners who will host it.”

Former Supremes member Mary Wilson said, “It happened in Detroit because Berry Gordy was there, and he gave us a place to go.”

Terry, who's also a Gordy — she's the granddaughter of the chairman’s eldest sister, museum founder Esther Gordy Edwards — affirms that. And she refers to what happened in 1959 as “lightning in a bottle."

"Everything just happened to work perfectly,” she said. “You had the visionary in Berry Gordy — songwriter, music maker. Then you add Hitsville to that, in a city like Detroit where music is in the DNA, it’s on every street corner, every school — churches, nightclubs. And then you have this untapped talent that now, suddenly, has a place to go. All of those things being present at one time created something very magical.”

Gordy was in Detroit because his parents, Berry Gordy Sr. and Bertha Fuller Gordy, had moved their growing family north from Georgia in 1922, where “Pops” Gordy picked cotton and eventually owned land (Berry Jr. was born here in 1929). Their offspring would soon number eight, in order of age: Fuller, Esther, Anna, Loucye, George, Gwen, Berry Jr. and Robert.

As bustling as Detroit was in the 1920s, it wasn’t easy for a black family to gain a foothold. The family’s early accommodations on the east side were rough, and young Berry had a vivid memory of his tough father killing rats in their kitchen with a shovel. Berry Sr. supported the family as a plasterer, then became a plastering contractor and bought a small grocery store. St. Antoine and Farnsworth streets on the east side were the center of Gordy operations. Each child was expected to work and learn.

“Pops” Gordy never smoked or drank, or scaled back on his work ethic, even at the age of 90. “I eat and drink the right things to build a healthy body, and I go to work every day,” he told The News’ society writer Eleanor Breitmeyer at his 90th birthday party in 1978.

Berry Jr.’s skill at construction work didn’t always measure up to his exacting father’s standards, but the determination seeped through. Commenting upon the innumerable takes he would subject his singers and musicians to, Gordy quipped, “Sometimes you have it perfect, but you just want it better.”

An important part of the Gordy ethos was that the girls worked just as hard, and were as accomplished or more so than the boys. Mother Bertha studied accounting, held a real estate license and sold life insurance door-to-door.

Esther Gordy Edwards, who founded the Motown Museum after her brother moved the company to Los Angeles, described the family philosophy to The Detroit News in 2003: “Be the best, strive for excellence, learn everything. My dad taught us girls how to change tires, we knew how to drive cars by the time we were 9 or 10 years old. Whoever can do a job best, let them do it. Some women can do better handling money than the fellows. Berry had more women vice presidents and above than any other corporation at the time.”

Detroit’s auto company infrastructure played a part; Gordy Jr. famously supported himself working as an $85-a-week upholstery trimmer on a Lincoln-Mercury assembly line, before he quit after selling songs to Jackie Wilson (“Reet Petite” and “Lonely Teardops,” to name just two).

Detroit radio was key: The R&B station WJLB played Motown records fresh from the Owosso pressing factory as fast as Gordy could get them to the station. The pop stations — WXYZ, WKNR and CKLW — were soon to follow.

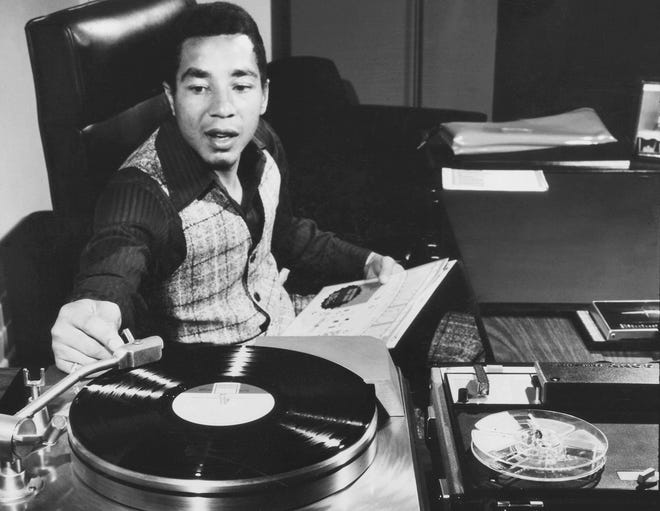

Several disc jockeys were key to Motown’s success locally, which then pushed the record company into regional and then national sales and airplay. The music mix coming over the Motor City’s airwaves was always pleasingly diverse, weaving country hits in with R&B and pop, mirroring the city’s demographics.

“Detroit made the difference, musically, because of what I heard here on the radio,” Stevie Wonder told The News in 1984. “There’s a kind of melting pot of different cultures and people here.”

One key disc jockey was WKNR’s Scott Regen, who hosted Motown Mondays at the Roostertail and hung out at Motown so much he became a staff songwriter.

“I was in sessions with Berry and Holland-Dozier-Holland. I’d just go in the building and walk around,” said Regen. “I knew them, they knew me. I’d walk into Norman Whitfield’s office and he’d be listening to ‘American Woman’ (by the Guess Who) over and over and over. I said ‘What are you doing ?’ Norman said: ‘I’m looking for a bassline.’ So, from ‘American Woman’ he got ‘Ball of Confusion,’ Regen said, laughing.

Another important air personality was “Frantic” Ernie Durham, to whom a young Stevie Wonder listened avidly from his home on Greenlawn.

Wilson recalls when she, Diana Ross and Florence Ballard got their first opportunity to sing before an audience — as the Primettes, no less — at a “Frantic” Ernie Durham sock hop. “Ernie would say, ‘Yeah, and we have our local girls, the Primettes!’ We didn’t have a record out, we were just singing everybody else’s hits. Our guitarist, Marvin Tarplin, would just do a live little jam session.”

One of the least-heralded factors in Motown’s success was the then world-class Detroit Public Schools’ music program. Artists mention teachers by name; Martha Reeves remembers Abraham Silver at Northeastern High School, and William Helstein at Northwestern High School encouraged bassist James Jamerson, one of the most revered musicians in pop history. Even Moore, DPS’s special school for discipline problems, had an inspirational choir director who helped put Levi Stubbs, drummer Uriel Jones and others on a better path, channeling their energy into music.

Rick Sperling, who just revived his “Motown 1962” musical for the Mosaic Youth Theater, recalls something Motown arranger Paul Riser told him during the first production of the musical.

“Paul said to me that people get the story of Motown wrong. They think Berry Gordy found these kids who sang in church, and gave them that chance — but people don’t talk about how we had the best music programs in the state, and possibly in the country, in Detroit. Paul was doing string arrangements at Motown when he was 19 years old, based on what he learned at Cass Tech. It wasn’t just an accident that Motown happened here.”

Detroit also had a world-class jazz scene in the 1950s, and Gordy — with the help of A&R director, Mickey Stevenson — scooped up an array of jazz talent from Detroit’s nightclubs, as well as from the band that played on Soupy Sales’ nighttime jazz program.

Why jazz players? Gordy liked to say that they were smarter than other musicians.

At Motown, the magic was created inside the modest recording studio by those jazz musicians sparking ideas off each other, giving writer/producers such as Smokey Robinson and Holland-Dozier-Holland earworm riffs and perfectly executed backbeats, doubling Jamerson’s masterful bass playing and always keeping the rhythm strong.

Given that tradition, Terry believes it’s important for the Motown museum to stress the human factor — individuals singing and playing musical instruments — the thing that led to its success.

“It’s part of our mission to make sure that music isn’t lost on this new generation,” Terry said. “They don’t get exposed enough to instruments. Paul Riser just did a panel discussion, and on the stage were some younger engineers and musicians, and they were talking about the way music was made today and the advantages of digital music. Paul said he appreciated the advancement of music and technology, but nothing can compare to being in a room with live musicians, and the ability to create and co-create when you put live musicians in a room. You can’t replicate that.”

One thing they may be able to replicate is the setting where Riser and other Motown personnel made magic. Terry said she has been talking to experts on the restoration of classic recording equipment — which is still in place in Studio A at Hitsville. Over the years musicians have wanted to record there, but bringing recording equipment in was the only option. To restore the original sound equipment is another thing entirely.

At the 60-year mark, even artists who have criticized Motown for its handling of their money have taken a softer tone. It’s not just that time has a way of healing old hurts, but Motown’s paternalistic system might not seem as harsh in retrospect, compared to the practices of other record companies of the time.

“I’m very, very proud to have been a part of Motown, and proud of artists like the Miracles, Marv Johnson and Mary Wells who really made it possible for us to go into the recording business,” said Wilson of the Supremes. “I’m happy that Mr. Gordy decided to bank his money on us. Some people are down on me because I’ve said so many things about Motown — but every company has things that you don’t like, things that happened that were not always the best for the artist. In the long run, I’m very happy to have been at Motown. I would have given up my grandchildren to sign with Motown — back then I just wanted to sing.”

The more she learns about Motown history — and there are always new stories to uncover — the more the museum’s Terry is proud of what happened here.

“Sometimes we can take it for granted when it’s in our own back yard,” Terry said. “When you really peel back the onionskin and look at all that talent coming out of one place that today, 60 years after, we’re still listening to and enjoying, and it’s relevant and being covered by brand-new artists . . . it just makes you go, wow. It’s not just special, it’s part of our culture, our world story, and it happened to have come out of Detroit.”

Susan Whitall is a longtime contributor to the Detroit News, and the author of Women of Motown (DeVault-Graves).