Detroit — Dennis Williams requested the meeting with General Motors Co. CEO Mary Barra because the United Auto Workers president wanted to deliver a message: He would support a merger of GM with Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV.

All GM needed to do in the spring of 2015 was agree to the blockbuster combination to realize ambitions FCA’s then-CEO, Sergio Marchionne, openly touted, even if a prospective deal imperiled plants, products and thousands of union jobs Williams was obliged to protect. The union leader's position defied projections of job losses, reinforcing rank-and-file suspicions their leadership had grown too close to management — and too willing to plunder union resources for their own benefit.

"The UAW's done its own research, and we think it's more favorable than you guys do," Williams told GM's leaders of Marchionne's latest proposal, according to two sources familiar with details of the meeting. "I think it's worthy of some study."

The suggestion essentially culminated Marchionne’s evolving strategy to gain control of old Chrysler assets from bankruptcy and to buy union support for his vision to create a global American auto colossus the Italian-born executive would control. Marchionne dismissed skeptics, instead insisting such a tie-up would not result in the plant closings and rank-and-file job losses GM said it would after its own board-level study of a potential combination.

In his second-floor president’s office adorned with football helmets and portraits of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., Williams parroted Marchionne's rationale to Barra, President Dan Ammann and CFO Chuck Stevens, according to a civil racketeering lawsuit GM filed against FCA in November. For at least the fourth time in three years, GM said no deal.

The $85 billion government bailout that 10 years ago rescued GM, delivered Chrysler Group to Marchionne's Fiat SpA for no cash down and gave the United Auto Workers large stakes in both automakers also fueled a decade-long corruption conspiracy that has tarnished FCA's revival, undermined the UAW's credibility and exposed the labor union to federal takeover.

Thousands of pages of federal court records, dozens of interviews with auto industry figures, lawyers and federal officials, as well as on-the-ground reporting in three states, help define the origins of the country’s largest union corruption scandal in 40 years and highlight the multimillion-dollar cost of a scheme hatched in the auto industry’s darkest hour.

"This is an ugly story," said Erik Gordon, a professor at the University of Michigan's Ross School of Business. "Pots of money from the government can be irresistible to people. It suggests that there is a culture of corruption and sort of a cozy collusion between the company and union brass" — a culture that an automaker could exploit.

Frank Hammer, 76, of Detroit is a retired UAW international representative and self-described dissident. He traces the roots of corruption to the “extremely hazardous cultural change” that happened after the union and the automakers began jointly operated programs and opened training centers in the 1980s, a move he saw as a threat to the union.

Fiat Chrysler executives, armed with $12.5 billion in taxpayer funds, started funneling bribes and illegal payments to UAW officials within days of the automaker emerging from bankruptcy in June 2009, The Detroit News has learned, partially squandering a second chance financed by American taxpayers. Prosecutors allege the money was part of a broad attempt by Fiat Chrysler executives to secure labor concessions from the UAW by keeping labor leaders “fat, dumb and happy.”

The government’s four-year investigation has revealed how labor leaders misused the bailout’s historic second chance by embezzling money from worker paychecks, shaking down union contractors and scheming with auto executives. The conspiracy stretched from the California desert and a union town on the banks of the Missouri River to the woods of Northern Michigan and the Jersey Shore.

"When the UAW goes on strike and the workers are making — I think it was $275 per week ... And what does the leadership get? Bottles of booze worth $1,300. Lavish steak dinners," U.S. Attorney Matthew Schneider, the Justice Department's top prosecutor in Detroit, told The News.

In all, UAW officials and auto executives are accused of misappropriating nearly $34 million since the bailout 10 years ago, according to an analysis by The News. That money includes embezzled member dues and funds siphoned from facilities that train roughly 150,000 of the union's nearly 400,000 members.

The timing of illegal payments within days of attaining control of Chrysler signals the importance Marchionne appeared to place on buying influence within the UAW, one of the nation's largest and most powerful labor unions. When the remnants of Chrysler emerged from bankruptcy, its UAW retiree health care trust owned a majority stake in the Auburn Hills automaker, and a close relationship with the union could buttress Marchionne's hope of one day acquiring GM, sources familiar with the investigation said.

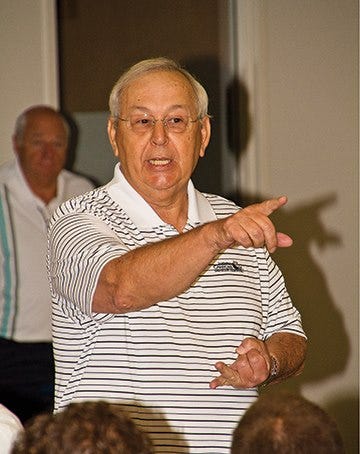

So far, 13 people tied to the UAW and Fiat Chrysler have been charged in federal court, and prosecutors have implicated at least seven others in the conspiracy. Those include Williams, the union's president emeritus, and recently resigned President Gary Jones, who is accused of stealing as much as $700,000 from workers and trying to cover up crimes. William's attorneys did not respond to requests for comment, and Jones' attorney declined comment.

Corruption Inc.

Before the UAW scandal erupted two years ago, public officials in Metro Detroit went to prison for receiving bribes that amounted to as little as a used purple Lexus and $10,025 worth of hair plugs.

The auto industry corruption crackdown, centered in America's Motor City, is establishing new benchmarks. Union leaders and auto executives have been accused of receiving an average of $422,000 in illegal benefits — twice as much as regional politicians and municipal employees convicted in the last decade.

"I do think it’s based on greed," Schneider said. "The instant that you decide to put your interests ahead of somebody else’s and serve your greedy or selfish interests, that’s it."

The corruption spanned at least four generations of UAW leaders, a mix of presidents, vice presidents and the union’s junior varsity. According to the government, there was a band of thieves at the UAW’s Solidarity House headquarters along the Detroit River, swindlers in regional offices in the heartland and shakedown artists on the East Coast.

UAW Vice President Joe Ashton headed an Atlantic City crew that strong-armed union contractors into paying kickbacks. The embezzlement squad in St. Louis was led by the late Region 5 Director Jim Wells, a hot-headed gambler who, until now, has not been publicly linked to the scandal, according to sources familiar with the investigation.

Colleagues describe Wells as a Svengali who taught subordinates how to skim member dues, including one bespectacled accountant named Gary Jones who last year took control of the UAW while continuing to skim money, according to prosecutors.

The crews committed crimes on their own and as a team, creating a national network of corruption connected most directly by three letters: UAW. Every December, the crews united in Palm Springs, where member dues and Fiat Chrysler cash financed a more than $1 million spending spree. Labor leaders spent freely on poolside villas, five-figure filet dinners and vodka poured from crystal skulls.

From 2014-15, UAW bosses spent member dues on 107 rounds of golf at the nation’s premier courses. With union money, they bought new golf clothes, rainbow-colored golf balls made in South Korea and golf equipment, including a $1,955 set of Titleist golf clubs.

Federal agents seized a matching set of clubs from the suburban Detroit garage of Jones, right next to where they seized more than $32,000 in cash during an August raid. The raid, as well as allegations Jones embezzled member dues, elevated the four-year investigation from a focus on comparatively minor labor law crimes to what legal experts describe as outright thievery.

The pots of money prosecutors say were tapped by UAW officials are dwindling as the investigation approaches its fifth year. GM and the UAW have agreed to shutter a training center financed with money that ended up in labor leaders’ pockets, and bargainers for FCA and Ford Motor Co. are dissolving their joint centers; union officials have mothballed nonprofit charities since investigators started questioning whether the UAW leaders personally benefited from donations; and federal agents are questioning whether union bosses drained accounts that were established to buy flowers for auto worker funerals.

The corruption scandal has proven costly for the UAW. Eight people linked to the union have been convicted so far. The UAW lost its seat on the GM board last year, a seat awarded during the Detroit automaker’s bankruptcy that was occupied by a retired vice president later accused of demanding $550,000 in bribes and kickbacks from a union contractor.

A sitting UAW president implicated in the scandal resigned as the union initiated steps to remove him, and his predecessor has been implicated, too. The scandal also has tarnished the UAW’s historic reputation as a clean union, a legacy of its longest-serving president, Walter Reuther. The UAW lost 35,000 members last year, and the ongoing investigation is expected to all but doom the union’s ability to lure new members in southern plants owned by foreign automakers.

And the four-year corruption investigation has exposed FCA to civil racketeering charges by crosstown rival GM, a target of Marchionne's quest to consolidate the two automakers into a global powerhouse Marchionne planned to lead. GM alleges the FCA CEO, who died two summers ago, masterminded a scheme to buy UAW influence to raise costs on GM, weaken it and engineer a merger.

In response, FCA pointed to a previous statement labeling GM's lawsuit a "meritless attempt to divert attention from that company’s own challenges." The Italian-American automaker said it "will deal with this extraordinary attempt at distraction through the appropriate channels and will stay focused on continuing to deliver record results."

The allegations against the UAW and ongoing investigation also have heightened the possibility federal prosecutors will file civil racketeering charges against the union. The move could result in the federal government taking control of one of the nation’s largest and most powerful unions, instituting broad reforms and removing current leaders.

Warning signs in plain sight

"Fat, dumb and happy" was in full flower by spring 2017. That's when an interior decorator dropped off a basket of white birch sticks at a cabin in northern Michigan.

The lakefront, wood-paneled cabin was being renovated by Williams, then UAW president, as part of a $10 million upgrade to the union’s Black Lake Conference Center, a 1,000-acre retreat near Cheboygan. The project was bankrolled after the first hike in membership dues in almost 50 years.

The increased dues, one answer to the union's worsening financial predicament, helped to replenish a depleted UAW strike fund. Besides paying for wages and medical and prescription drug benefits for striking workers, the $750 million fund also finances operations for the conference center dating back to the Reuther era.

Flush with cash for the renovations, Williams outfitted the cabin with a humidor and wine cooler, according to a source. He also commissioned a larger retirement home for himself on an adjacent property that would soon draw the interest of FBI agents. And it eventually would be built with nonunion labor.

But first, Williams needed a few final decorations. He arranged for an interior decorator to bring baubles and decorative pieces, including the basket of white birch sticks that carried a $150 price tag. The expense struck UAW officials familiar with the cabin project as frivolous because a few feet from the cabin's front door stood a forest of white birches, their branches free for the taking.

Such spending ran counter to the mandate Williams inherited from his election in June 2014: repair the UAW's finances and boost membership. That included raising member dues 25%, even as corruption fueled by those same dollars flourished.

By spring 2017, life within the upper echelon of the UAW was far removed from the Great Recession that threatened the union's existence and the U.S. auto industry just eight years earlier. UAW membership was up more than 21%, automakers were booking fat profits and more membership dues were flowing into UAW coffers.

Williams cut costs and increased revenue. But the way he did it would soon draw attention from a team of federal agents from the FBI, Internal Revenue Service and Labor Department. They were told by a top aide to Williams that he had saved the union money by offloading travel and entertainment expenses to Fiat Chrysler, the No. 3 Detroit automaker run by his old friend, Marchionne.

Fiat Chrysler executives poured more than $100 million into the Detroit joint-training center it operated with senior officers from the UAW, according to court records and tax filings. Fiat Chrysler Vice President Alphons Iacobelli — a Harvard-trained executive with exotic hobbies that included collecting solid-gold fountain pens and Italian-made, cherry red roadsters — handed those labor leaders credit cards paid for by the automaker and encouraged them to swipe liberally.

"If you see something you want," Iacobelli told UAW officer Nancy Adams Johnson in July 2014, according to federal court records that recount the conversation, "feel free to buy it."

How it started

Iacobelli was the automaker's top labor negotiator when what's now called Fiat Chrysler exited Chapter 11 bankruptcy in June 2009 with $12.5 billion in federal aid and a new leader, Marchionne. That's when Iacobelli, his company's point man with the UAW, admitted to opening the financial spigot.

Starting that month, authorities say, Iacobelli and Fiat Chrysler made more than $9 million in illegal payments over eight years to the UAW to cover salaries and benefits of union officials assigned to the training center. Some of those officials worked at the center, but for a large number of UAW officials these were no-show jobs, prosecutors said in a sentencing memo. Iacobelli and Fiat Chrysler viewed the payments as "a political gift" to the UAW.

"It was merely a corrupt mechanism whereby FCA money could be used by the UAW to keep the UAW’s costs down," Assistant U.S. Attorney David Gardey said in court filings. The payments violated a federal law — the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 — barring company officials from giving money or things of value to labor leaders.

The UAW also collected a 7% fee in addition to the $9 million paid for the no-show jobs, according to prosecutors. Starting in June 2009, that fee pumped an additional $2.9 million into the UAW's bank account, ostensibly to cover administrative costs.

"FCA viewed the 7 (percent fee) as simply another cost of doing business with the UAW in terms of keeping labor peace," Gardey said.

On Sept. 29, three months after Fiat Chrysler left bankruptcy court, Iacobelli met with the automaker's financial analyst, Jerome Durden. At the time, Durden controlled the books of the UAW-Chrysler training center and was a close friend of UAW Vice President General Holiefield, the burly labor leader assigned to the union's Fiat Chrysler department.

During the meeting, Iacobelli talked about restarting an internal Fiat Chrysler plan to funnel money to "high value/high leverage programs," according to a Durden email summarizing the meeting. The email referenced one such program: the nonprofit "Leave the Light On Foundation," a charity for poor children headed by Holiefield. Durden served as the charity's treasurer.

"The overall tone of the meeting," Durden wrote in the emails, "was a desire to deliver some good news to the UAW for a change."

The meeting transformed the foundation from a purported charity into a Trojan horse used by Iacobelli, Durden and others to hide illegal payments. The payments were designed to keep Holiefield happy and to extract favorable labor concessions for Fiat Chrysler, prosecutors said. Durden pleaded guilty in 2017 to making illegal payments to Holiefield and others.

Between 2009 and 2015, Iacobelli and others steered more than $1.2 million in illegal payments to Holiefield, wife Monica Morgan-Holiefield and others. The payments included first-class airfare, clothing, jewelry, furniture; $13,300 to pay for the Holiefields' pool; and $262,219 to pay off the mortgage on their home in suburban Detroit.

Iacobelli was not a rogue auto executive breaking labor laws that bar management from giving labor officials money and things of value, his lawyer, David DuMouchel, said: "Mr. Iacobelli joined an already ongoing conspiracy. The practices and corruption that are the focus of this case started long before Mr. Iacobelli."

And prosecutors say Iacobelli answered to one person on UAW matters: Fiat Chrysler CEO Sergio Marchionne.

The sweater-clad CEO forged a close relationship with Holiefield, who headed the UAW-FCA Department and led national contract talks with the automaker. Keeping Holiefield happy was a priority for Marchionne and his executive team.

As his team funneled bribes to Holiefield, Marchionne seduced him with gold — a mustard-yellow, limited-edition watch in February 2010, eight months after the Fiat Chrysler bankruptcy concluded.

The Terra Cielo Mare, part of the Italian watchmaker's line of custom-made timepieces, featured the Fiat logo and retailed for $2,245. At that price, the average UAW member would need to work two weeks on the assembly line to afford one.

The watch came with a hand-written note: “Dear General, I declared the goods at less than fifty bucks. That should remove any potential conflict. Best regards, and see you soon,” according to federal court records obtained by The News.

Federal investigators later asked Marchionne whether he had given UAW leaders valuable items when he was questioned during a secret meeting at the U.S. Attorney's Office in downtown Detroit in July 2016, sources told The News.

Nope, Marchionne said. Investigators then confronted the CEO with evidence about the timepiece. The meeting ended with Marchionne exposed to federal charges. But the 66-year-old, accused in GM's civil racketeering lawsuit of masterminding the decade-long bribery conspiracy, was never charged with a crime before he died in July 2018 in a Zurich hospital.

Prosecutors have labeled the auto company a co-conspirator, along with the UAW and the training center, in a conspiracy to violate federal labor laws. Fiat Chrysler is negotiating a settlement that could cost the company less than $50 million.

How the feds got wise

The federal crackdown on auto industry corruption started with a right-hand man and a cherry red roadster.

In September 2013, Holiefield’s top aide, James Hardy, abruptly left the UAW amid allegations he was selling jobs at Chrysler plants. Hardy cooperated with federal investigators and was never criminally charged. But he gave federal investigators a window into the UAW’s internal affairs, as well as a deeper understanding of how the union’s Fiat Chrysler department was plagued by corruption.

A few months later, on May 15, 2014, Iacobelli walked past palm trees and into the exotic car dealership, Naples Motorsports, in southwest Florida. He zoomed out with a red 2013 Ferrari 458 Spider convertible and installed an “IACOBLI” vanity plate on the $365,482 exotic car.

The conspicuous purchase drew attention from federal investigators who analyzed financial records and determined the Ferrari was purchased with money that was supposed to pay for UAW blue-collar worker training.

The Ferrari and Hardy led to a sprawling investigation that would push the UAW to the brink of federal oversight, reshuffle the top ranks of the U.S. auto industry and expose Fiat Chrysler executives as schemers bent on warping the collective bargaining process. It also would form the basis for the civil racketeering lawsuit from arch-rival GM alleging that FCA, led by its CEO, systematically bribed union leaders in a conspiracy to raise GM's labor costs to force a merger.

While Marchionne was handing out watches in Italy, a separate scheme was underway 7,614 miles from Turin at a UAW regional office in a suburban St. Louis. And corruption big and small flourished in one of America's most iconic auto towns, Flint, the home of the sit-down strikes, the vast Buick City complex and the stress of GM's decades-long retreat.

The Hotspot Flint

Corruption infiltrates lower levels of UAW leadership, too, said Kathy Otto, former president of UAW Local 326 and 1292. “Each director in Region 1-C-D had their club that you were encouraged to donate to, although it wasn’t required," she said, confirming she was approached by regional staff about paying into these clubs when she was elected.

► INTERACTIVE: A Database of corruption in Detroit

She describes a system of political patronage. Members in good standing would get preferential treatment in conflict resolutions, to speed their ascension through the leadership ranks, to burnish their standing among union brothers and sisters.

“I felt that if you're not part of the club, you're not going to get the help," Otto said. "My thought was that I was elected just like they were, and I shouldn't have to donate to some slush fund. Some think that they're privileged. They're not. They're servants.”

The groups sported quirky names that rhymed, an apparent union tradition. Norwood Jewell, the former regional director in Flint who abruptly resigned as vice president and director of the FCA department before his conviction on federal charges, had one, too, confirmed Otto and John Gleason, Genesee County clerk and a former member employee at GM Flint Truck Assembly.

“When you try to do the right thing, it’s constant harassment,” said Gleason, who added he found about 50 spikes thrown in his driveway three times in 2016 after supporting a county politician the UAW wasn’t backing. An investigation into the incidents is ongoing.

He has organized rallies calling for the removal of Jewell’s name from all union property, especially the memorial honoring sit-down strikers in front of the UAW Region 1-D office in Flint. Gleason’s grandfather was one of them.

“If the corporation wasn’t abusing its employees, we would never have had a union,” Gleason said. “What they started to end, they have since joined. It’s disgusting. I’m absolutely disgusted.”

Jewell, sentenced in August to 15 months in federal prison for accepting bribes, is not the only product of the Flint culture swept up in the federal crackdown. Mike Grimes, 65, of Fort Myers, Florida, pleaded guilty in September to federal charges of wire fraud conspiracy and money laundering. The government said Grimes received $1.5 million in bribes and kickbacks from union vendors.

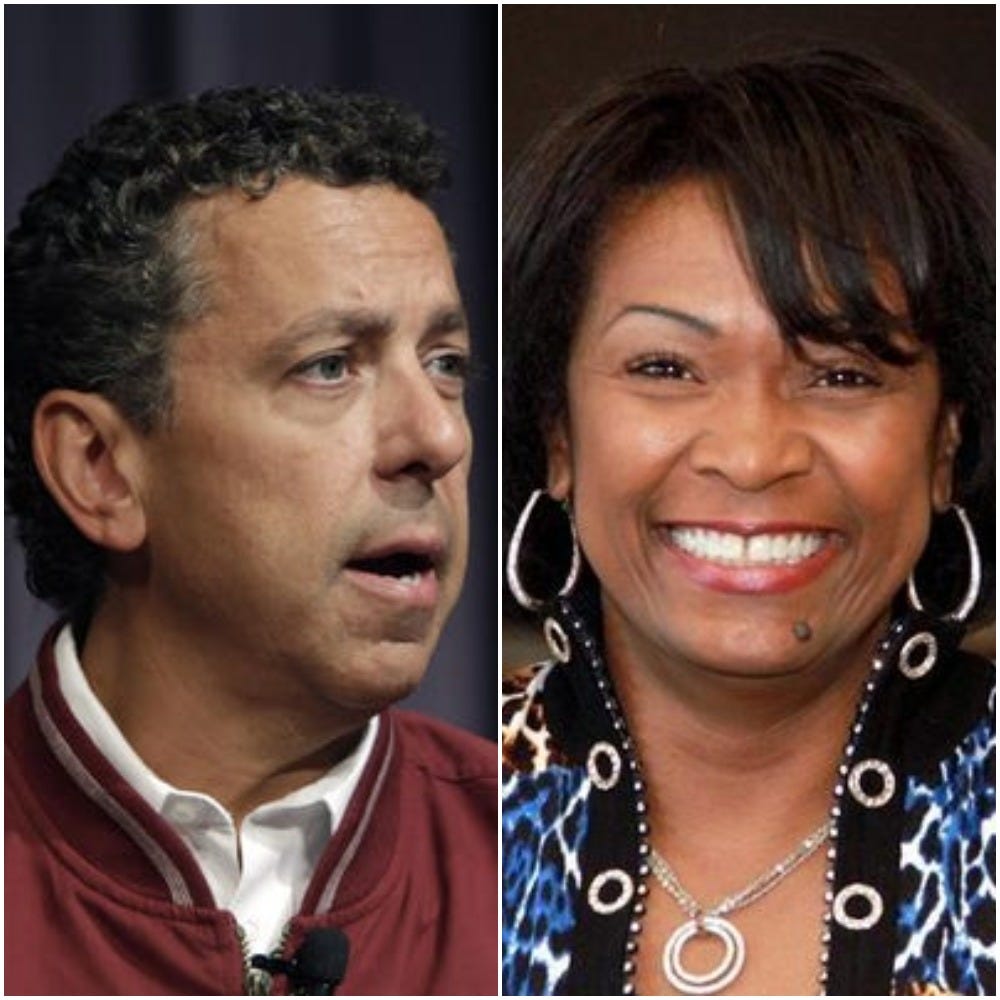

People who worked with Grimes, both in the union and at GM, expressed shock that he could be implicated in the federal crackdown. He was administrative assistant to UAW Vice President Cindy Estrada when she headed the union's GM Department, and Estrada says Grimes "would have been the last person I ever thought would do that. I've never been more shocked in my life — and hurt and angry. "

Frank Hammer and Grimes worked in the GM Department as international representatives. Hammer was surprised when Grimes was charged with collecting kickbacks from vendors to the Center for Human Resources, a jointly operated training center between the UAW and GM that is funded by the automaker.

"He was one of the guys I thought that was on the higher end of the spectrum in terms of doing his job and so on," Hammer said. "He has fallen and succumbed to the temptations."

Hammer blames the alleged partnership between union leaders and management, epitomized by joint training centers like the UAW-GM Center for Human Resources on the Detroit River known derisively as "the palace."

"The idea was they were going to build on this cooperative relationship. It would be a whole system from the shop floor to the top leadership where this partnership was fertilized and grown.” And that partnership, Hammer believes, led to corruption.

“UAW officials began to view themselves as co-managers, and they got to the point where they said, ‘we ought to get the perks, too.’ In this new era of managerial partnership, I think some of them convinced themselves they deserved what their managerial co-partners had. I think some of them really began to think that way.”

The scam back east

In the fall of 2012, a bribery and kickback scheme involving different UAW officials was intensifying along the East Coast. Like the St. Louis crew long headed by the late Jim Wells, the East Coast ring involved a UAW power broker poised to reach the union's governing International Executive Board.

His name was Joe Ashton, a regional UAW director in Atlantic City who celebrated his 40th anniversary in the union when GM was in bankruptcy court a decade ago. His job included organizing blackjack dealers and other casino workers — until he moved on to bigger things in Detroit.

Ashton was named a UAW vice president and director of its GM Department in June 2010. His new duties included helping to operate the UAW-GM Center for Human Resources, an impressive training facility financed by GM. The CHR, also known in some UAW-GM circles as the "Center for Hidden Relatives," survived GM's 2009 bankruptcy in part because the automaker received a taxpayer bailout totaling nearly $50 billion.

"The UAW played a key role in GM's comeback story," Ashton said in 2012, "and the game has really just begun."

So had a multimillion-dollar bribery and kickback game involving money from post-bankrupt GM. In 2012, Ashton conspired with top aide Jeff Pietrzyk and Grimes to demand bribes and kickbacks from training center contractors. In return, Ashton and the aides steered more than $15.8 million worth of contracts for UAW-branded clothes and trinkets, including jackets, backpacks and watches.

The contracts were paid with money from GM that was supposed to train blue-collar workers. Grimes pleaded guilty in October after being accused of helping steer contracts to vendors, including a family-operated business that sold American-made custom logo clothes and accessories — and paid more than $1 million in kickbacks and bribes to Grimes.

The criminal case offered insight into a merchandise industry colloquially called "trinkets and trash." The market includes a collection of companies vying for a share of the more than $29 million spent by the UAW and related groups in the last five years on promotion, advertising and union-branded items.

INTERACTIVE: Trinkets and trash, a database of UAW spending on swag

Ashton, meanwhile, chose a more intimate target for a shakedown. In 2012, he devised a plan to give every union worker at GM plants a watch, a gift meant to symbolize the quality vehicles and the strong partnership between GM and the UAW.

Ashton contacted his Philadelphia-based chiropractor, Marc Cohen, and told him to create a company that could win the contract and supply the watches, according to the government. After Cohen won the $3.97 million watch contract, according to court records, Ashton demanded a $250,000 kickback in spring 2013.

The 58,000 watches were delivered Jan. 31, 2014, a date that proved to be unfortunate. Six days later, GM started to recall about 800,000 vehicles due to a faulty ignition switch, the first public indication of a fatal flaw blamed for the deaths of 124 people.

The watches were never distributed. Yet Ashton's career kept rising thanks, in large part, to the GM bankruptcy. In August 2014, Ashton joined GM's board of directors, replacing Vice Chairman Steve Girsky as representative of the UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust. The UAW acquired the board seat during the 2009 bankruptcy in part because its health care trust was, at the time, GM's largest shareholder.

Ashton's career fared better than the watches — temporarily, anyway. As recently as August, the timepieces were languishing in boxes on pallets in a Detroit warehouse. And earlier this month, Ashton pleaded guilty in federal court to charges of wire fraud and money laundering in the corruption scandal.

California, here we come

Once a year, the East Coast kickback crew, the union leaders from Flint and the UAW's Detroit power structure converged on the desert oasis of Palm Springs with what prosecutors described in a Sept. 12 criminal complaint as an embezzlement gang from St. Louis.

The Region 5 group included several generations of UAW officers assigned to the union's largest geographic territory. They worked out of an industrial office in suburban St. Louis. Among them was Wells' successor, Gary Jones, the future UAW president who once served as the union's chief accountant back at Solidarity House.

As Region 5 boss, Jones hosted annual regional conventions in the California desert from 2014 to 2018. The events drew the union president, vice presidents, regional directors and local officers with unofficial titles — including, sources say, the bubble wrapper tasked with packing bottles of leftover booze in luggage and shipping the liquor back home.

Palm Springs continues to play a central role in the ongoing investigation targeting Jones and Williams, the union's two most recent presidents. Prosecutors say the two CEOs conspired with others to embezzle more than $1 million in union funds spent in Palm Springs and Missouri on poolside private villas, top-shelf liquor, cigars, golf and more.

Region 5 conferences in Palm Springs lasted as long as five days. Yet UAW leaders stayed for months, prosecutors said, turning the five-story Renaissance Palm Springs Hotel on East Tahquitz Canyon Way into Solidarity House West, far from cold Michigan winters.

“They came out here for years,” said Steve Fitzharris, the club professional at Desert Princess Country Club, where Labor Department filings show the UAW spent $96,806 in 2014 to rent private villas lining the course. “They were a bunch of nice guys. Normally" their golf events "were very well run."

The expenses, hidden from regulatory scrutiny under a master billing scheme devised by senior union leaders, included more than $6,599.87 for a New Year's Eve meal in December 2016 — $1,942 on liquor, $1,440 on wine, a $1,100 tip and the purchase of four bottles of Louis Roederer Cristal Champagne for $1,760.

When it was time to leave, a UAW vendor loaded luggage, new golf clubs and leftover booze into a tractor-trailer and drove back to Detroit. Union leaders left nothing behind, except evidence of fancy goods bought with someone else's money.

"The vendor also transported the luggage back to Detroit as well as any luxury items that were purchased in and around Palm Springs by the UAW officials," Labor Department Special Agent Andrew Donohue wrote in a court filing, describing a "culture of alcohol" within the senior union ranks.

Sergio's endgame

By 2015, Marchionne wouldn't quit.

Three years earlier, in 2012, his proposed merger with GM received scrutiny from the automaker's top three executives — all Wall Street deal-makers before coming to Detroit. Led by then-CEO Dan Akerson, Girsky and President Dan Ammann conducted an extensive review of a potential combination between GM, Fiat SpA and Chrysler.

They evaluated multiple combinations ranging from joint powertrain ventures and brand acquisitions to a complete merger of what were then three entities. Potential impediments included anti-trust concerns, political backlash, the likelihood that promised "synergies" would not be realized.

Most of all, GM's leaders concluded such a combination would require cutting jobs, brands, products and plants. They worried the cuts would be especially damaging for a metro Detroit region just beginning to recover from the Great Recession and the bankruptcies of GM and Chrysler — worries Marchionne routinely dismissed in favor of his industrial logic and repeated pledge to not endanger "the blue collars."

"By 2014, FCA Group had been rejected repeatedly by GM regarding a merger between the two companies," GM alleges in its civil racketeering lawsuit against FCA. "But in early 2015, having successfully consolidated control over Chrysler and positioned FCA NV for merger, FCA believed it was in a much stronger position to force a GM merger."

In a nearly four-page letter dated March 9, 2015, that was reviewed by The News, Marchionne wrote Barra and then-Chairman Theodore Solso to once again propose a merger between the two companies. The FCA boss said the combined company would stake a "formidable position" in North America and would create a "solid platform" in Europe, among other things justifying his take on the deal.

What he didn't say: the combination would be greased by the support of UAW President Dennis Williams, who could invoke Document 13 of the national UAW-FCA contract to block a merger — or let one proceed. Additionally, the union president wielded practical control over the UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust, whose stake in GM could be materially affected should a multibillion-dollar GM-FCA transaction raise the value of its holdings.

Under GM's 2009 agreement with the U.S. Treasury Department, the UAW's shares must be voted proportionately with the remaining shareholders. That makes it nearly impossible for the union health care trust to support or block a proposed merger, despite then having a representative on GM's board — namely, Ashton, convicted earlier this month of wire fraud and money laundering.

But the union itself could support a deal.

On April 14, 2015, GM again rejected Marchionne's proposal. Two weeks later, he used FCA's five-year markets presentation in Auburn Hills to unveil "Confessions of a Capital Junkie," Marchionne's manifesto for industry consolidation doubling as a public appeal to GM. The message was clear: He wouldn't quit.

The next gambit came two months later, delivered by Williams on June 18, the same day he told the media the UAW would "not support anything that would hurt our members." Barra, Ammann, Stevens and Cathy Clegg, GM's lead labor negotiator, joined Williams and Estrada, head of the union's GM Department, in Williams' office, according to the GM lawsuit.

The UAW president outlined the inevitability of industry consolidation, according to two sources briefed on the meeting, and warned that GM risked being left behind if the automaker failed to seriously consider Marchionne's latest proposal. But a team of outside lawyers, bankers, financial advisers and crisis communications consultants assembled earlier in the year by GM to fend off Harry Wilson, an activist investor, had studied the proposal — and reached a conclusion similar to the one three years ago.

No deal, in part because doing one with a crosstown rival would lead to plant closures that could devastate the UAW membership. Why Williams would even suggest such a combination mystified GM's leadership, and it would take at least two more years before an explanation began to emerge in the outline of a federal crackdown on union corruption.

"I can't imagine it ever happening," Estrada told The News, adding she "would have remembered" Williams backing a merger. "It's just insanity. Why would we ever be for a merger that had product overlap and plant closings?"

A potential answer came just a month later when FCA and the UAW held their ceremonial handshake to open 2015 national contract talks. Marchionne and Williams embraced, violating decades of protocol designed to depict the two sides as adversaries, not friends. UAW-FCA members rejected their first tentative agreement, called "transformational" by Marchionne, even as Williams hailed the next and final contract as the UAW's "richest" ever.

In its lawsuit, GM effectively says the 2015 UAW-FCA contract terms served as the culminating payoff in a Marchionne's years-long scheme to buy the support of UAW leadership at the expense of its largest U.S. competitor. It's a charge GM likely will be challenged to prove in its civil racketeering lawsuit against rival FCA.

The corruption exposed by the federal crackdown extends far beyond the UAW-FCA joint-training center in Detroit, or whatever the friendship between Williams and Marchionne may have portended. The continuing investigation is revealing a pervasive culture of self-dealing that also festered outside the orbit FCA began to create a decade ago.

Marchionne carried to the grave his bid to persuade an American partner to build a next-generation industry automotive giant, potentially with the help of the UAW. But the high price for corrupt practices begun soon after the automaker's taxpayer-funded bailout in 2009 continues to be paid — mounting costs for a culture of corruption inside the union Reuther built.

daniel.howes@detroitnews.com

rsnell@detroitnews.com

Auto writers Kalea Hall contributed reporting from St. Louis; Breana Noble contributed from Flint; and Ian Thibodeau contributed from Palm Springs, California.