Feds: Mich. only state to need special ed intervention

Jennifer Chambers

Jennifer Chambers

Michigan is the only state in the nation that failed to meet federal special education requirements and requires intervention, according to a U.S. Department of Education evaluation.

Federal education officials rated Michigan's annual performance on meeting the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, for the 2016-17 school year as "needs intervention."

Federal officials use both compliance and results data for a “letter of determination” on whether a state "meets requirements," "needs assistance" or "needs intervention."

Michigan’s rating came from its high drop-out rate and low graduation rate for students with disabilities, education experts say, as well as its poor performance in results data, which includes student assessments.

In Michigan, for students ages 3 through 21, federal education officials said:

- 29 percent of children with disabilities dropped out of school and 63 percent graduated with a regular high school diploma. That's compared to 15 percent and 74 percent in Massachusetts, for example, a state that meets federal IDEA requirements.

- 19 percent of eighth-graders with disabilities and 39 percent of fourth-graders scored basic or above in math on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP. In Massachusetts, it was 46 percent for eighth-graders and 59 percent for fourth-graders.

- 22 percent of fourth-graders and 34 percent of eighth-graders scored basic or above in reading on the NAEP, compared to 45 percent and 56 percent respectively in Massachusetts.

Michigan is the only state to receive the "needs intervention" ranking, alongside Washington, D.C., Palau and Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. Commonwealth.

It is the first year Michigan fell into the category after landing on the "needs assistance" determination list for the last four school years.

Officials with the Michigan Department of Education said on Monday they are still reviewing the report and assessing its content. They declined further comment.

The determination letter — first issued June 28 and then revised July 5 — rates the state's performance on two parts of IDEA: serving students ages 3 to 21 and serving infants to age 2.

Michigan received $366 million in grants in 2016-17 for students ages 3 to 21.

In a second category, which serves infants through children age 2, Michigan is meeting federal requirements of IDEA.

If a state needs intervention for three consecutive years, the U.S. Department of Education must take enforcement action, including requiring a corrective action plan or compliance agreement, or the state faces future federal payments being withheld. It's unclear how much funding would be at risk.

U.S Department of Education officials declined to comment further on the report, only saying that it "will continue to work with all states, including Michigan, to raise expectations and improve results for children and youth with disabilities and their families."

On June 28, Sheila Alles, Michigan's interim state superintendent, received a letter from Ruth Ryder, acting director at the Office of Special Education Programs at U.S. Department of Education, informing her of the rating. The letter was obtained by The Detroit News.

"OSEP appreciates the state’s efforts to improve results for children and youth with disabilities and looks forward to working with your state over the next year as we continue our important work of improving the lives of children with disabilities and their families," Ryder's letter said.

Candace Cortiella, the director of the Advocacy Institute in metro Washington, D.C., a nonprofit that works on behalf of people with disabilities, said the letter is significant and is one barometer for the public to understand how states are being held accountable for children with disabilities.

"The state is doing an unsatisfactory job on the academic achievements of students with disabilities in the state," Cortiella said. "The state needs to pay attention to outcomes, not just compliance with IDEA."

Some districts have targeted improving special education, such as the Detroit Public Schools Community District, which announced last week that it was implementing a widespread new special education plan that would target current failures in the system, including repeated noncompliance with student identification, IEP implementation and disciplinary procedures for special education students.

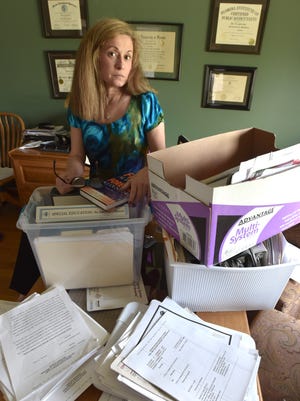

About 200,000 children have Individualized Education Plans, or IEPs, in Michigan, said Marcie Lipsitt, a Michigan-based special education advocate and civil rights activist. Children who are eligible for special education services can have IEPs, but not all families elect to get one.

Lipsitt, who has filed more than 2,400 federal civil rights complaints on special education compliance, saw the letter of determination and said special education conditions continue to erode in Michigan because of a lack of transparency at the state education department and insufficient funding for special education services.

In 2017, Michigan's Special Education Reform Task Force said a $700 million gap exists between the cost of current special education services and existing special education funding streams.

"Michigan has dropped further and further.... The result is children with disabilities are suffering every year. The outcomes are nothing more than egregious," Lipsitt said.

"It's never been more important for MDE to be the state education department they need to be, for all 200,000 children with Individual Education Plans and all Michigan children," she said.

Jeannine Somberg, a parent of a special education student in Macomb County, said she is not surprised at the state's poor performance.

"Federal and state laws are in place to be followed. I feel sorry for special education families in the state of Michigan. It is so dismal right now...It's truly a civil rights issue," Somberg said.