Analysis: Michigan maps show bias as gerrymandering heads to Supreme Court

Jonathan Oosting

Jonathan Oosting

Lansing — Michigan’s congressional maps continued to favor Republican candidates in 2018 even though Democrats flipped two seats to split control of the state’s delegation in a wave election, according to a new analysis.

And its state House boundaries ranked among the most biased in the country.

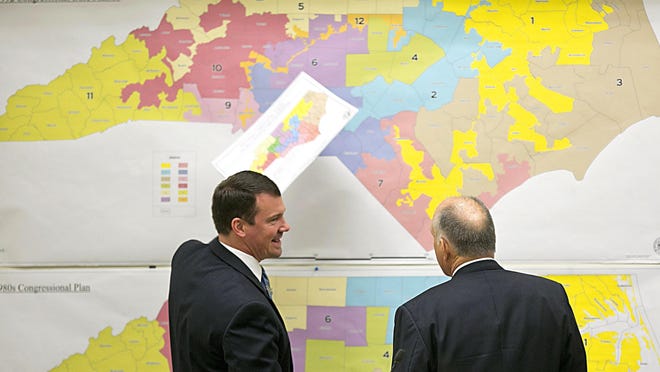

“Efficiency gap” measurements calculated by The Associated Press challenge GOP claims in the U.S. Supreme Court, which is set to hear oral arguments next week in alleged partisan gerrymandering cases from North Carolina and Maryland as Michigan judges consider a similar lawsuit here.

In a recent high court briefing, attorneys for the Republican National Committee and the National Republican Congressional Committee pointed to Michigan’s 2018 elections as evidence that courts are incapable of determining partisan intent.

“The ‘durability’ of Michigan’s partisan gerrymander was apparently limited to elections prior to 2018,” lead GOP attorney Jason Torchinsky and his colleagues told the Supreme Court justices, noting Democratic gains last fall.

“Time and time again courts have determined electoral maps to be unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders due to those maps’ effect of 'entrenching' a political party in power and then subsequently, under those same maps, the supposedly ‘entrenched’ party was defeated, sometimes in spectacular fashion.”

Michigan congressional districts, drawn by Republicans and first implemented in 2012, did show smaller signs of partisan bias in 2018 than in other recent years, according to the AP analysis of election data across the country.

But Michigan’s 8.1 percent efficiency gap score for 2018 was the 18th highest in the country and suggests Republican candidates won one extra congressional seat than would have been expected based on their vote share.

Democratic congressional candidates won 54 percent of major party votes in Michigan, compared with 46 percent for Republicans. They flipped two seats to split the state’s 14 U.S. House seats, seven to seven.

Nationally, Democrats regained control of the U.S. House and flipped hundreds of seats in state Legislatures. But the cycle was not as bad as it could have been for Republicans, whose strong 2010 election cycle put them in position to draw decade-defining maps in many states, according to the AP analysis.

“These districts are gerrymandered, but they’re not built for a thousand-year flood,” said Michael Li, senior redistricting counsel for the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law.

Republicans who drew district boundaries in Michigan and other states seven years ago had no way to foresee factors that shaped 2018, he said, including the 2016 election of President Donald Trump and unusually high voter turnout last fall.

“It’s like saying I had a seven-foot wall and then a hurricane came and it still flooded my property,” Li said.

Measuring bias

The efficiency gap, a relatively new formula cited in Supreme Court arguments, measures wasted votes for losing candidates and votes for winners beyond what was needed to triumph. It’s a way to gauge the impact of “packing” and “cracking” voters into certain districts to minimize the power of the minority party.

The apparent impact of Michigan’s partisan map-making process was more pronounced in state House races. Michigan’s 10.87 efficiency gap score ranked fourth highest in the country for 2018, suggesting nearly 12 excess seats for the GOP, according to AP calculations.

Democrats won 54 percent of the major party statewide vote, but Republicans won 53 percent of state House races, returning a 58-52 majority in the 110-member chamber.

Critics say the efficiency gap does not prove partisan gerrymandering and can produce “false positives” because of naturally occurring geographic factors and other legal requirements, including mandates for districts with a majority of African-American or other minority voters.

Rural areas in Michigan, including the Upper Peninsula, have increasingly turned Republican in recent years.

“In many states, Democratic voters are concentrated in or near urban areas while Republican voters are more evenly distributed,” attorneys for North Carolina Republicans said in a recent Supreme Court filing.

“As a result, the pre-existing political geography of the State will tend to produce more 'wasted' Democratic votes than Republican votes as long as the map drawer follows traditional districting principles like compactness, contiguity, and preserving communities of interest.”

Experts say the efficiency gap alone does not prove a partisan gerrymander, and the North Carolina and Maryland cases going before the Supreme Court include other evidence lower courts have used to determine partisan intent.

In North Carolina, lawmakers openly discussed partisan intent and a legislative committee adopted a criterion holding that the new makeup of congressional maps would continue a 10-3 majority for Republicans.

The efficiency gap and other statistical evidence can “raise red flags” in states like Michigan that are worthy of additional exploration by courts, Li said.

Geographic factors and a desire to keep communities intact “for any number of good or moral reasons” could play a role in an efficiency gap score, he said.

“In some states, you actually would have to gerrymander to get zero because there’s sort of a natural bias there.”

Michigan decision looms

The North Carolina case before the U.S. Supreme Court alleges a statewide gerrymander by Republicans, while the Maryland case alleges gerrymandering by Democrats to flip a specific congressional seat.

The Michigan suit alleges an unconstitutional Republican attempt to dilute the power of Democratic voters in congressional and legislative districts across the state and seeks an order for new maps in 2020.

GOP attorneys had asked the Supreme Court to delay the Michigan case, arguing its resolution would directly affect deliberations here. The court declined the request in February without explanation, and the case proceeded to trial that month.

Any Supreme Court decision will “likely supersede or control the ruling of the district court,” said Gary Gordon, an attorney representing some of the GOP lawmakers who have intervened in the Michigan case.

Republicans argue Michigan mapmakers followed all applicable laws when drawing congressional and legislative districts in 2011.

Emails produced in the case have shown mapmakers used software that calculated the partisan makeup of each district they drew and told Republicans they were providing options “to ensure we have a 9-5 (congressional) delegation in 2012 and beyond.”

The Supreme Court case gives justices the opportunity to “finally lay out the standard for what constitutes a partisan gerrymander,” said Li, who is part of a Brennan Center team that filed a legal brief supporting claims of unconstitutional partisan bias in the North Carolina and Maryland cases.

“That would help the court in Michigan and the courts elsewhere that are sort of wrestling with how to write opinions.”

The Michigan trial concluded in February and judges have since rejected two GOP motions to dismiss the suit or strike evidence. But it’s unclear if they will rule before or after the Supreme Court, which could do so by the end of June.

The impact of the high court ruling on the Michigan suit may depend on whether it is broad or narrowly focused on specifics of the North Carolina or Maryland cases, Li said.

“The Michigan case will be appealed to the Supreme Court as well,” he predicted, “and so it’s unclear to me if the court has any incentive to rush something out, other than at some point Michigan will need maps for the 2020 election.”

Michigan voters last year approved a ballot initiative to create a new citizen redistricting commission that will draw new congressional and legislative district lines, beginning in 2022. Previous state law had allowed whichever political party controlled the Michigan Legislature to control the process.

That continues to be the case in a majority of other states, meaning a Supreme Court decision could have a large impact heading into a 2020 election cycle that will decide who controls the process in those parts of the country.

“The court will be setting some ground rules for when maps are redrawn in 2021, and that’s going to be important because the data and the technology to do these sorts of gerrymanders are becoming more available and more powerful,” Li said. “People will slide and dice and recombine voters in ways that you would have only dreamed about in 2011.”

joosting@detroitnews.com