Expert: Michigan maps show 'historically extreme partisan bias' for GOP

Jonathan Oosting

Jonathan Oosting

Detroit — Michigan Republicans used their power in state government to benefit their party at the expense of Democratic voters, plaintiffs claimed Tuesday in opening arguments of a high-stakes federal trial alleging unconstitutional gerrymandering.

“The evidence shows we had this very secretive program, an intense program and a well-financed program to dilute the votes of voters of the opposite party to entrench the party in power,” the plaintiffs' attorney, Jay Yeager, told the three-judge panel overseeing the case.

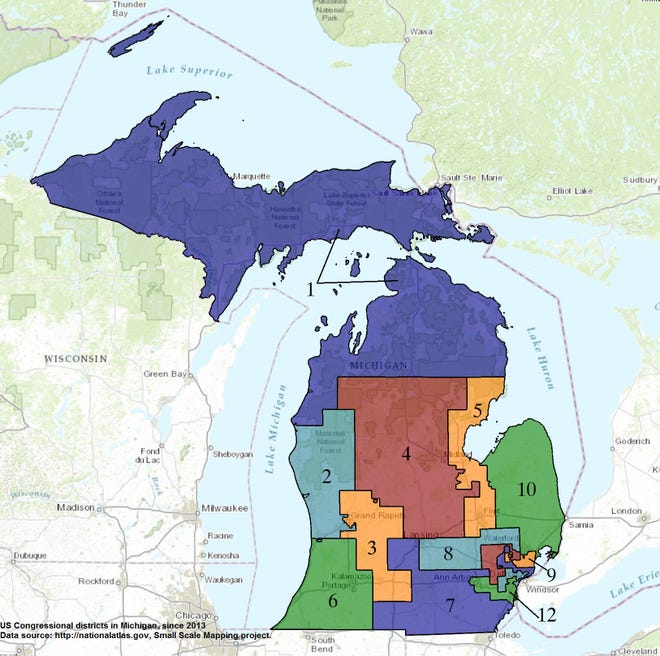

Plaintiffs contend GOP mapmakers who drew the state’s current legislative and congressional districts in 2011 “packed” or “cracked” Democratic voters into certain districts to minimize their impact and protect majorities. They’re seeking an order to redraw districts for the 2020 elections.

But Democrats are demanding court relief for what is actually a “naturally occurring political geography problem” without a legal solution, argued Jason Torchinsky, an attorney for state House and congressional Republicans.

Michigan Democrats “are highly concentrated in a handful of urban areas, and a similar pattern occurs across the rest of the country,” Torchinsky said, referring to Detroit and other regions. “When one party’s voters are highly concentrated, it becomes harder to translate those statewide votes into proportional seats.”

Geography could be one factor that has helped Michigan Republicans maintain legislative majorities, but it does not explain why multiple measurements show a significant rise in partisan district bias between the 2010 and 2012 elections, said Christopher Warshaw, an assistant political science professor from George Washington University.

Michigan maps approved by the GOP-led Legislature in 2011 produced a “historically extreme partisan bias in favor of Republicans that was consistent between 2012 and 2016” and appears to have continued in 2018, said Warshaw, who testified for the plaintiffs.

The trial opening here at the Theodore Levin U.S. Courthouse came after days of drama and attempts to settle the case out of court or postpone it indefinitely.

The federal panel on Friday rejected a proposed consent agreement between plaintiffs and Democratic Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson that would have forced reconfiguration of at least 11 state House districts for 2020. The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday denied a GOP request to delay the Michigan case as justices consider separate gerrymandering cases out of Maryland and North Carolina in March.

Warshaw compared Michigan's state House, Senate and congressional elections between 2012 and 2016 to hundreds of other elections across the country over the past 45 years using three separate measurements of partisan bias, including a formula called the efficiency gap that identifies “wasted” votes by opposition party voters.

Expert dings GOP maps

Michigan’s congressional districts were more pro-Republican than 98 percent of all congressional maps, Warshaw said. State House districts had a larger pro-Republican bias than 99.7 percent of all previous maps, and 2014 state Senate districts had a larger bias than 98 percent of all maps created nationwide since 1972.

“In your opinion, is that the kind of thing that happens by accident?” asked Yeager, the plaintiff attorney.

“No,” said Warshaw, whose research helped prove a GOP gerrymander in Pennsylvania.

The data-heavy testimony prompted multiple questions from judges, requests for clarification and pleas for Warshaw to slow down. “I’m having trouble following this,” District Court Judge Gordon Quist said at one point.

GOP attorney David Cessante challenged the measurements that informed Warshaw’s conclusions, noting that scholars have not agreed on any precise range of efficiency gap scores to determine what amounts to an “unacceptable” gerrymander.

“Some political scientists don’t even agree the efficiency gap is capable of measuring partisan bias,” Cessante said. “If the efficiency gap isn’t capable of distinguishing between a wasted vote due to a partisan gerrymander versus a legitimately wasted vote, what’s the point?”

He also pressed Warshaw to acknowledge that the efficiency gap does not measure the impact on any particular voter, a potential important distinction as plaintiffs are attempting to prove specific harm to individual Democratic voters.

"If there's no evidence of a partisan gerrymandering existing today, in 2019, then nothing needs to be done with the maps," Cessante said, noting Warshaw only analyzed Michigan district results through 2016.

Warshaw acknowledged scholarly debate over the efficiency gap but noted he used two other measurements to confirm an “average effect” on Michigan voters. He argued his research is more than just an academic exercise or game because Democrat and Republicans pursue “vastly different” policies when elected.

Trial expectations

The trial is expected to take roughly one week and will include testimony from GOP mapmakers, redistricting experts and Democrats who argue they have been marginalized because of current legislative or congressional maps.

The suit was filed on behalf of several Democratic voters and the League of Women Voters of Michigan, whose past president was the first witness called to testify for the plaintiffs.

Susan Smith of Ypsilanti said she is a Democratic voter in the 12th Congressional District and 18th state Senate District, which are “packed” with other Democrats.

“I know that no matter how I vote, a Democrat is going to win the general election,” Smith testified. “If I wasn’t packed in with so many Democrats, I might have more influence in another district as to the outcome of a particular election.”

Smith said she attended a state Senate committee hearing in 2011 and was dismayed when majority Republicans quickly approved district lines that were described on paper only by census tracts that she could not understand.

“I could not figure out what district I was in,” she said. “After sitting through that hearing and seeing the lack of transparency, the lack of public involvement, the lack of even communicating what the maps were at that point before they voted on them, that’s when I thought, ‘Wow, the league has got to get involved.’”

GOP: Map rules followed

Republican attorneys noted mapmakers who drew the 2011 districts were required to follow several laws, including population requirements, the Michigan Apol standards that generally discourage county or municipal line breaks, and preclearance for two areas federally mandated under the Voting Rights Act.

“To the extent that politics was considered, it was subordinate to these other factors,” said Torchinsky, telling judges that it should come as no surprise that lawmakers had a motivation to protect their own seats or majorities.

Michigan Democrats picked up legislative and congressional seats in 2018, he noted, suggesting claims of a durable gerrymander have proven wrong in other states.

Democrats flipped two U.S. House seats in 2018 and now represent seven of the state’s 14 congressional districts. Fellow GOP attorney Shawn Sheehy pointed out the split was the most common projection in thousands of computer-generated maps produced by plaintiff expert Jowei Chen of the University of Michigan.

Sheehy also noted that a Democrat for whom Smith has voted, then-state Sen. Rebekah Warren of Ann Arbor, voted for the 2011 redistricting plan in the Legislature.

Should the court rule that unconstitutional gerrymandering occurred, it would be “improper” for the court to force state Senate elections in 2020, said attorney Gary Gordon, who represents some of the GOP intervenors. State senators now in office were elected last year to serve four-year terms through 2022.

“It would violate the terms of office for which these people are elected and would require them to run for three elections in a matter of six years,” Gordon said. “The Senate is designed to be a four-year institution.”

Proving discriminatory intent

Plaintiff attorneys are attempting to prove the Legislature had discriminatory intent to dilute the power of Democratic voters and that the maps they approved in 2011 would continue the discrimination if used again in 2020.

Michigan voters last fall approved the creation of an independent redistricting commission that will draw new political district lines for 2022 and beyond.

Yeager highlighted a series of documents obtained by plaintiffs last week after the court rejected claims of attorney-client privilege for weekly GOP redistricting meetings at a law firm.

“Now that we have had a spectacular election outcome, it’s time to make sure the Democrats cannot take it away from us in 2011 and 2012,” said a November 2010 memo from the Republican National Committee.

That memo from “before the gerrymander started” shows the national Republican Party was already offering input to Michigan mapmakers, warning of likely lawsuits and recommending talking points, Yeager said.

Attorneys for Republican lawmakers are challenging whether plaintiffs have “standing” to challenge the maps, why they waited for three election cycles to file the complaint and whether there are any accurate methods to measure gerrymandering.

The panel overseeing the case is comprised of Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Eric Clay, District Court Judge Denise Page Hood and Quist. Clay and Hood were both appointed to the bench by former President Bill Clinton, a Democrat, while Quist was appointed by former President George H.W. Bush, a Republican.

Gordon, in his opening statement for state Senate Republicans, blasted what he called “out-of-context emails” and expert analysis that “makes a good headline” but does not prove intentional gerrymandering.

While experts have used computer programs to draw “better” maps, “better doesn’t matter as long as the plan adopted by the Legislature is constitutional,” Gordon argued.

joosting@detroitnews.com