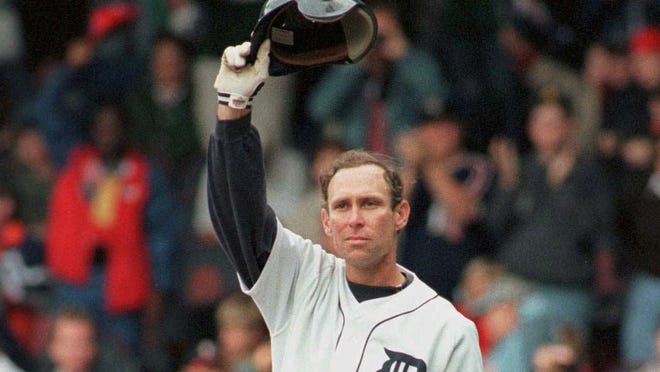

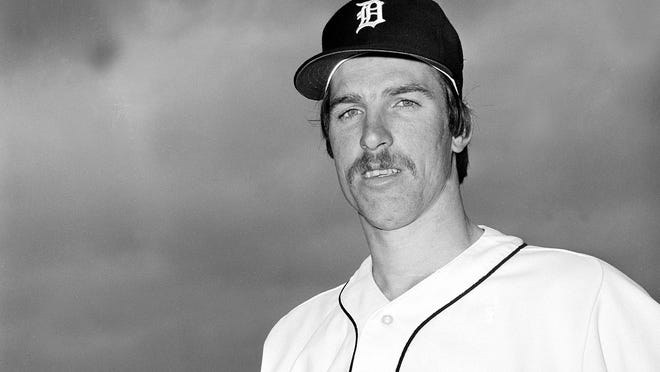

Double play: Tigers' Alan Trammell, Jack Morris make Hall of Fame

Orlando – They together helped deliver Detroit’s last baseball championship in 1984, and now Alan Trammell and Jack Morris are headed to baseball’s Hall of Fame.

Trammell, a magnificently polished shortstop and sturdy hitter, joined Morris, a furious right-handed starter, when they were announced Sunday evening as winners following a vote by the Modern Era Committee. They will be enshrined in July at Cooperstown, New York.

“Going in with Jack is meaningful,” Trammell said in a national teleconference Sunday night. “I’ve been asked, especially lately, ‘Are they overlooking our team?’ That answers that. They can put that to rest.

“I never really got into that. If they did overlook us, so be it. We can’t do anything about it. But I am really happy we are going in together. Fans get attached to players of certain eras and I could sense that for Tigers fans all across the country, it meant a lot to have one of us get in. Now they have two.”

Morris, in a separate teleconference, echoed Trammell’s sentiments.

“This certainly gives us a sense of pride,” he said. “I know Tigers fans have been loyal since that year and I know we brought them some joy. And I know a lot of people in Michigan always wondered why a team that was so good, so dominant had nobody represent them in the Hall of Fame?

“I am proud that Alan and I made it together. I can’t imagine a better scenario than to go in with a former teammate and a guy I love and respect so much. It’s going to a good day, a warm and fuzzy day for Tigers fans. The tradition of Tigers baseball is magnified because we’re finally getting acknowledgment for that ’84 team.”

Trammell is the first career Tigers player since Al Kaline in 1980 to be installed within a baseball sanctuary considered to be the most prestigious of all such halls of fame. Trammell and Morris were among nine players appraised by the Modern Era Committee, a 16-person group assigned to review elite players whose careers factored heavily in a span from 1970-87. Other players considered were Dale Murphy, Dave Parker, Don Mattingly, Steve Garvey, Luis Tiant, and Tommy John, as well as Southfield native Ted Simmons. Marvin Miller, the lawyer who helped make the players’ union a dynamic force in sports commerce, was also considered.

Trammell and Morris were the only two elected Sunday.

“Playing for the Tigers was truly a privilege and to go into the Hall of Fame as a Tiger is a milestone that I am thrilled to now share with both of them,” Tigers great Al Kaline said. "I am honored that they will join those who wear the Olde English ‘D’ in Cooperstown.”

Trammell's No. 3 and Morris' No. 47 will be retired by the Tigers during a ceremony in August at Comerica Park, Christopher Ilitch, President and CEO of Ilitch Holdings announced Sunday.

“I am proud to have been a Tiger my entire career,” Trammell said. “There aren’t many baseball players who can look at the back of their baseball card and say they played for the same team for 20 years.

“That might not mean a lot to some people, but it means a heck of a lot to me.”

More: What they’re saying about Alan Trammell, Jack Morris

Trammell won Sunday for the simple fact his case was so compelling. He had a marvelous 20 seasons that compared neatly with another shortstop who five years ago crashed Cooperstown: Barry Larkin.

Trammell’s two-way excellence was enhanced by his consistency. He was a seamless, if unspectacular, defender. He had an average throwing arm. But he positioned himself in model fashion, often squaring up a ground ball, scooping it smoothly into his glove, and in one graceful over-the-top throw delivering a near-perfect throw to first. Thousands of times he made such plays, appearing almost mechanical in his fielding sequence and efficiency of motion.

He could also hit. Trammell’s best season was 1987, when he batted .343, slammed 28 home runs, and somehow missed winning the American League’s Most Valuable Player trophy. He lost that year to Blue Jays slugger George Bell, who had a blazing first half and whose soft finish seemed not to be noticed by voters who made Bell the choice over Trammell.

“I guess I had come to the realization that it might not happen,” Trammell said when asked if he’d lost hope of winning induction into the hall. “And I was OK with that. I didn’t want to get caught up in, ‘What’s going to happen to me if I don’t get in.’ I wasn’t going to do that. I knew that I could play and that’s how I viewed it.

“If people felt it was a tad short, then I could live with that. But we can turn the page on that. If I’m a utility infielder coming in on a Hall of Fame All-Star team, I am OK with that too.”

Morris had come closer than Trammell during his 15 years on the Hall of Fame docket. He got as much as 67.7 percent of the vote, with 75 percent required for election.

Morris’ case was strong: He won 254 games during his 18 seasons, 14 of which were spent with the Tigers.

And while his 3.90 ERA is the highest of any Hall of Fame pitcher, and his career strikeouts (2,478 in 3,824 innings) were no greater than 34th on the all-time list, his overall luster and durability, helped by his ace-like mastery for two World Series-winning teams, made him a victor Sunday when the Modern Era voters convened at Lake Buena Vista, Fla., scene of this week’s Winter Meetings.

“It’s overwhelming to know I finally made it,” Morris said. “Because I did taste it. I was close and it just didn’t work out. The last few years, I wasn’t angry at the writers. I was confused as to why it didn’t happen. I wasn’t angry because I finally came to realize how difficult it was for them.”

Suddenly Morris found his career being devalued by analytics that weren’t part of the game in the era that he pitched.

“For years my ERA has been an issue for a lot of people who thought it was not good enough for Hall of Fame honor,” Morris said. “But I never once thought about pitching for ERA. I always thought about starting games and finishing games and winning games more than anything else.

“I am not making that as an excuse. But my mindset was winning that game. It didn’t matter if it was 7-8 or 1-0. I was just as happy either way.”

Those arguing his case had been passionate about Morris, with particular emphasis on his 1991 World Series virtuoso in which he threw a 10-inning masterpiece, with the Twins winning in the 10th, 1-0, to nip the Braves for the world championship.

“That was my defining moment in baseball,” he said. “It was the only Game 7 I ever pitched and also, I was at the apex of my career both mentally and physically. I never pitched a game where I had better focus.”

Trammell’s and Morris’ triumphs were perhaps bittersweet for some Tigers followers, as well as for those who insist Trammell’s double-play partner, Lou Whitaker, is every bit as worthy of induction as Trammell, and who even more has been slighted by past votes.

Whitaker fell off the 2001 ballot in his first Hall of Fame bid. He failed to get even 5 percent of the writers’ vote, the bare minimum to remain in contention. He lost again when the 2018 Modern Era review excluded him from this autumn’s 10-man re-exam. His career Wins Above Replacement was 74.9, well above the norm (69.4) for Hall of Fame second basemen.

Whitaker also slammed 244 home runs and had a career OPS of .789, which included, amazingly, an .800-plus OPS in each of his final five seasons. But his candidacy remains bogged down, either because voters fail to be moved by his compelling career numbers, or, perhaps, because of a personality that during his playing days leaned toward the obscure.

As much as Sunday’s vote cheered Trammell fans, it was bound to be celebrated by the Tigers, who haven’t had a career Tigers player reach Cooperstown since Kaline did it in 1980. The Tigers’ glee might speak also to an amazing relationship between a man and a lone big-league club. Trammell’s time with the Tigers could have ended, perhaps bitterly, and even permanently, when he was fired as Tigers manager following the 2005 season after the team had gone through a gruesome reconstruction.

But he never publicly took a single shot at his old ballclub. He soon took a coaching job with the Cubs and later joined his old teammate, Kirk Gibson, when Gibson managed the Diamondbacks. He returned in 2014 when late Tigers owner Mike Ilitch and Detroit’s front office invited him to work as a special assistant to the general manager – a coaching/scouting position in which he has flourished.

Morris had a different path during his 18 years in the big leagues. He left the Tigers as a free agent following the 1990 season and signed with his hometown Twins. He later pitched for the Blue Jays and Indians.

Twitter @cmccosky

Twitter @Lynn_Henning